This month’s SCDot6 post is given over to two dear friends on the occasion of the Celebration of Life for one and the incredibly poetry she inspired in the other.

There are hundreds of articles and videos and tributes written by and about Judith Snow. She was just as influential and funny and pointed and impatient and thoughtful as those pieces make her out to be.

Judith challenges us to question our assumptions about what folks can and cannot do and where they can and cannot live. She thumbed her nose at our low expectations and exhortations about safety. Yes, it took a whole team of folks — her circle of support — to get her out of that institution and into “the community”, but, ironically, Judith created community wherever she was and that institution was hardly a barrier to her — except that it was.

So, dear one, on this 6th day of June, question your assumptions. Then do it again on June 7. And again on June 8.

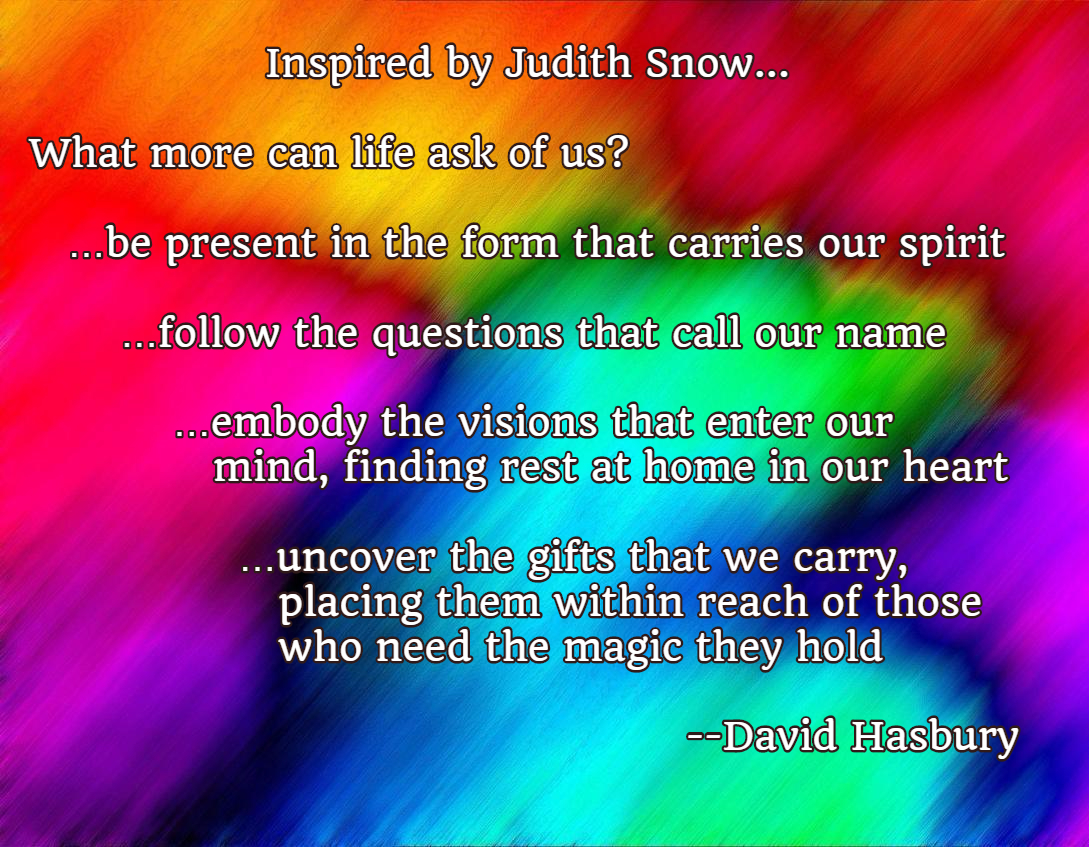

David Hasbury — a deep thinker in his own right — captures it so well in his grief-and-gratitude-laced poem.

We’re sad, but we celebrate.

And we keep on truckin’.

—-

The image is a colorful, painted background with David Hasbury’s poem written on top of it.

Inspired by Judith Snow…

What more can life ask of us?

…be present in the form that carries our spirit

…follow the questions that call our name

…embody the visions that enter our mind, finding rest at home in our heart

…uncover the gifts that we carry, placing them within reach of those who need the magic they hold

your thoughts